A Physician’s Guide to the High Mountains

From the warm and humid coasts of Udupi to the icy winds of Everest Base Camp, I have felt the dramatic shift in how our bodies handle the world. I have walked the trails to Kedarnath. I have stood at Gangotri and trekked to Gomukh. I have marveled at the beauty of Kullu Manali and the pristine peak of Jungfrau in Interlaken, Switzerland.

The mountains call us. They offer silence and majesty. But as a physician, I must tell you that they also offer a significant physiological challenge. Anyone who travels to high altitude, whether a recreational hiker or a pilgrim, is at risk of developing high-altitude sickness. The air gets thin. The pressure drops. Your body struggles to grab the oxygen it needs. This is not just about fitness. It is about biology.

Whether you are a pilgrim, a trekker, or a skier, you must respect the altitude. Let us discuss how to stay safe.

The Thin Air

When we go high, specifically above 2500 meters (about 8200 feet), the barometric pressure drops. There is less oxygen available for every breath you take. Thouugh the percentage of oxygen in the air is the same (21%), the its partial pressure drops as we go higher up.

Your body reacts immediately. The initiating event is cerebral vasodilation in response to hypoxemia. This means your brain vessels become wider to try and get more blood and oxygen. This causes an increase in brain volume and pressure inside your skull.

“The mountain demands humility. It forces us to realize that our strength is borrowed from the very air we breathe.”

For some, this swelling is minor. For others, it causes problems. There is a concept called the “tight fit” hypothesis. If your brain fits tightly inside your skull, you have less room for the swollen brain, making you more symptomatic. Generally, as we age, our brain shrinks slightly and has more room to accommodate the swelling.

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS): The Common Enemy

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is the most common high-altitude illness. Think of it as a severe alcohol hangover, but without the fun of the party the night before.

What to look for:

It usually starts 6 to 12 hours after you arrive at a new altitude. It can happen as low as 2000 meters, but it is very common (in 25 percent of people) at sleeping elevations between 2000 and 3000 meters.

- Headache: This is the primary symptom.

- Nausea or Vomiting: You lose your appetite.

- Fatigue: You feel incredibly tired.

- Dizziness: A sense of lightheadedness.

- Sleep Issues: You wake up frequently.

Who gets it?

Everyone is at risk. Neither youth nor physical fitness gives you protection against AMS. In fact, younger males might sometimes be at risk because they continue to climb in spite of having symptoms.

Your oxygen saturation (SpO2) measured by a finger probe is not a perfect test. You can have normal oxygen levels and still have AMS. However, a high-normal value is unusual if you are sick. Trust your symptoms more than the machine.

When It Gets Dangerous: High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

If you ignore AMS and keep climbing, you risk High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). This is a life-threatening emergency.

HACE is essentially “brain swelling” that has gone too far. It typically troubles you above 3000 meters. The fluid leaks into the brain tissue.

The Red Flag Signs of HACE:

- Ataxia: Imbalance. This is the hallmark sign. The person walks like they are drunk. They cannot walk a straight line.

- Confusion: They become irritable, drowsy, or stop making sense.

- Coma: If untreated, they will lose consciousness.

A person with HACE might just want to be left alone in their tent. They might say they are just tired. Do not leave them alone. This “lassitude” is a symptom of the brain failing.

Prevention:

I have seen many travelers spoil their trip by rushing. In places like the majestic Ladakh or on the way to Kedarnath, people fly or drive up too fast. The single best prevention is gradual ascent. Walking up gives us the natural slow ascent that helps avoid AMS.

The Golden Rules of Ascent

- Go Slow: Above 2500 meters, try not to increase your sleeping elevation by too much in 24 hours.

- Acclimatize: Spend a day or two at intermediate altitudes.

- Medication Prophylaxis: If you must ascend quickly, or if you have a history of sickness, medicine helps.

| Method | Recommendation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetazolamide | Preferred. 125 mg every 12 hours. | Start the day before ascent. It accelerates acclimatization. |

| Dexamethasone | Alternative. 2 to 4 mg every 6 hours. | Use if allergic to acetazolamide. It stops symptoms but does not help with acclimatization itself. |

| Gradual Ascent | Essential. | The most effective natural method. |

Acetazolamide (Diamox):

This medicine is my preferred tool for prevention. It creates a bicarbonate diuresis with metabolic acidosis. This stimulates your breathing, which rapidly improves oxygenation. I have taken this on most of my high-altitude treks.

Side effects: It is a diuretic, so you will urinate more. You might feel tingling in your fingers.

Treatment: What to Do If We Get Sick

If you or your trekking partner gets sick, you must act. Do not hope it will just “go away” if you keep climbing.

Treating Mild AMS

You can usually stay where you are and just take rest.

- Stop Ascending: This is non-negotiable.

- Rest: Limit physical activity.

- Symptom relief: Use paracetamol or ibuprofen for headache. Use ondansetron for nausea.

- Acetazolamide: You can take 125 to 250 mg twice daily to help treat the illness.

Treating Severe AMS or HACE

If the person is confused, cannot walk straight (ataxia), or if the headache is severe and vomiting is frequent, you are in danger.

- Descent: This is the definitive treatment. You must go down. Even descending 500 to 1000 meters can save a life.

- Oxygen: If available, give oxygen immediately to keep saturation above 90%.

- Dexamethasone: This is a potent steroid. Give 8 mg immediately (oral, IV, or IM), followed by 4 mg every six hours. It reduces brain swelling and can buy you time to walk down.

- Hyperbaric Bag: In remote areas without oxygen (like high camps on Everest), professional mountaineers use a portable hyperbaric chamber (Gamow bag). It uses air pressure to simulate a lower altitude.

Advice for Your Next Trip

Whether you are seeking the divine at Kedarnath, the raw challenge of Everest Base Camp or the thrill of the slopes in Switzerland, carry this knowledge with you.

- Plan your itinerary with buffer days. Allow days for rest and unexpected delays.

- Hydrate, but do not overdo it.

- Avoid alcohol; it depresses your breathing during sleep.

- Watch your friends. If they act strange or stumble while walking, it is not fatigue. It is the altitude.

“There is no such thing as bad weather, only inappropriate clothing.”

– Ranulph Fiennes

This is not just a motivational quote. In the high mountains, it is a medical fact. The Himalayan weather is very moody. It can swing from blinding sunshine to a freezing blizzard in under twenty minutes. In such conditions, your clothing is not just for style… it is your first line of defense against hypothermia.

As trekkers, you must master the ‘Layered Clothing System’. Think of it like an onion. You need a base layer to wick away sweat, a middle layer to trap body heat, and an outer shell to block the wind. If your clothing is appropriate, you can stand on a glacier at -15°C and feel comfortable and enjoy the surroundings. If it is inappropriate, even a mild wind can become a medical emergency.

“We do not conquer the mountain. We only conquer ourselves, and we do so by listening to what nature conveys to us in the thin air.”

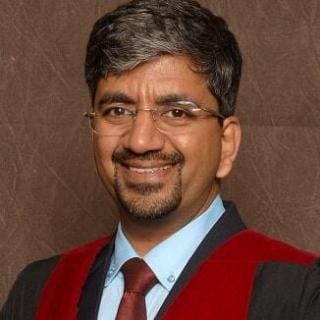

Dr. Shashikiran Umakanth (MBBS, MD, FRCP Edin.) is the Professor & Head of Internal Medicine at Dr. TMA Pai Hospital, Udupi, under the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE). While he has contributed to nearly 100 scientific publications in the academic world, he writes on MEDiscuss out of a passion to simplify complex medical science for public awareness.