The Uncertainty We Drive Through

This is Part 1 of Sadgati: Safe Passage on Shared Roads, a three-part reflection on road safety.

In our culture, the word ‘Sadgati’ generally means the salvation attained after death or reaching the feet of the Almighty. However, looking at the condition of traffic on our roads today, if someone sets out in a vehicle and returns home safely to their loved ones without any threat to their life, that safe arrival itself has become the true ‘Sadgati’. Don’t you agree?

Last Sunday, I asked my daughter to drive from Mangalore to Udupi.

She has a licence. Not much experience though. And experience doesn’t come from theory… it comes from actually driving on the road. So she took the wheel. I sat in the passenger seat.

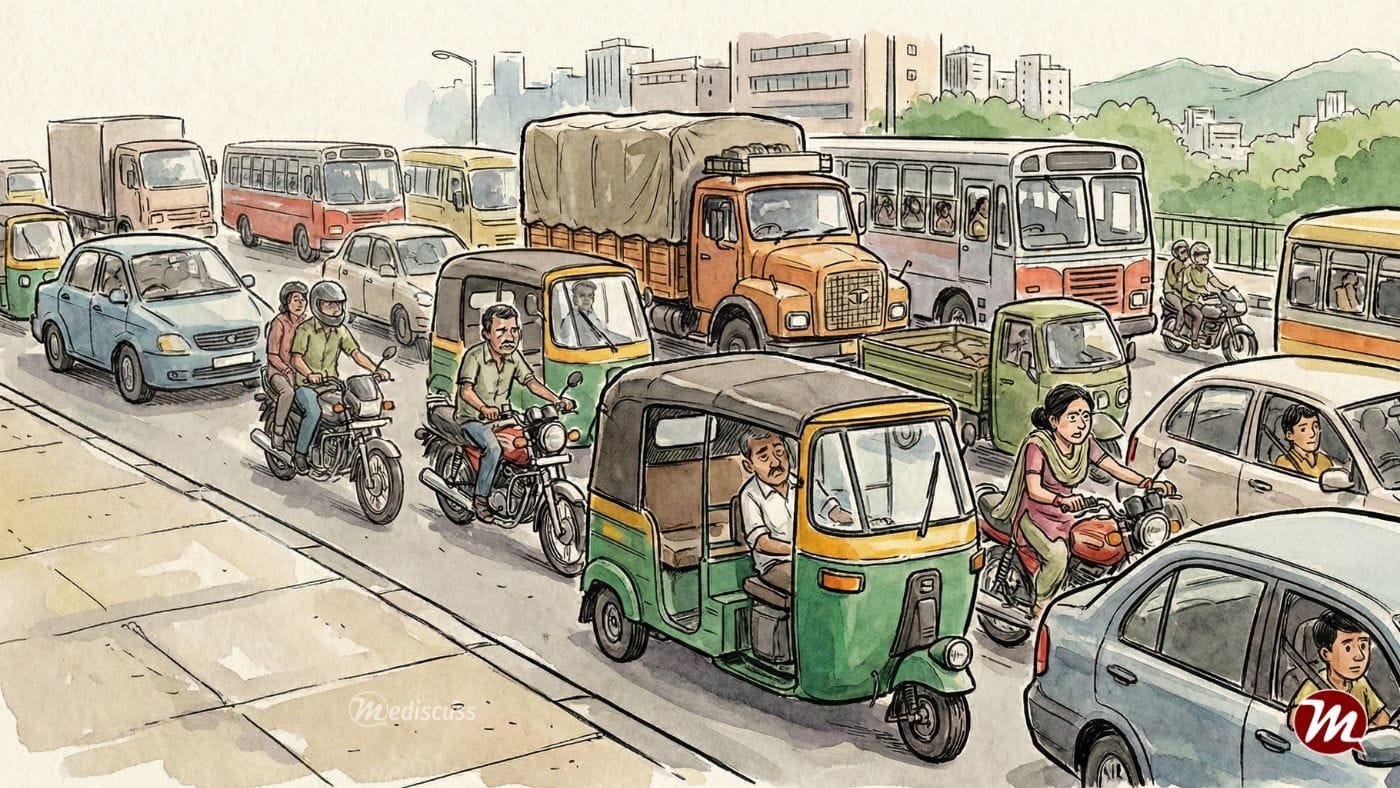

Within minutes, we both noticed the same thing. Not traffic. The unpredictability.

A truck drifted across lanes without warning. A motorcycle slipped through gaps that seemed impossibly narrow. An SUV pressed right up behind us, clearly impatient with our compliance to the speed limit. No pattern. No rhythm. Just multiple individual decisions colliding in shared space.

She glanced at me. “How much of my safety depends on me, and how much on everyone else?”

I didn’t answer immediately.

Because the honest answer is unsettling. Even perfect driving can’t guarantee safety. On the road, outcomes are shared.

Ancient Indian philosophy, especially Buddhism, has a word for this interdependence: pratītyasamutpāda, the principle that outcomes arise not from isolated actions, but from interconnected causes. Modern traffic engineering confirms what dharmic thought recognized millennia ago – your fate and mine are woven together the moment we enter the road.

What I’ve Seen From Both Sides

I’ve been driving for over three decades now. Not just in coastal Karnataka, but across most of southern India, through the ghats, along the highways, in congested city centers. I have also experienced different parts of the country during my years in North India.

Everywhere, the fundamental challenge remains the same. We share space with strangers whose minds we can’t read, whose states we can’t assess, whose next move we can’t predict.

I haven’t driven in other countries, but I’ve been on the roads there as a passenger and pedestrian. Europe, America, Japan, Southeast Asia, the Middle East. What struck me? The way societies handle this uncertainty varies dramatically.

In Japan, traffic moves with almost choreographed precision, like clockwork. Not because Japanese drivers are born with that skill, but because their culture enforces a collective understanding: your behavior affects everyone else. Lane discipline is absolute. Turn signals aren’t optional favours, they’re obligations.

In much of Europe, the infrastructure itself seems designed to prevent catastrophe. Roads compensate for errors. Speed limits adjust to conditions. Pedestrian zones physically separate vulnerable road users from vehicles.

In India, we rely far more heavily on individual alertness and reflexes of each driver. The system demands more from each driver because there is less structural support. India accounts for about 11% of global road traffic deaths in spite of having only 1% of the world’s vehicles. 1

And we see the consequences in hospitals. The motorcyclist whose collarbone shattered when someone opened a car door without looking. The senior citizen with a severe brain concussion after being hit while walking on the roadside by a drowsy driver. The elderly woman with hip fractures after a vehicle jumped into the footpath.

These victims weren’t careless people. They were ordinary individuals who happened to be in the wrong place when the attention of someone else lapsed, judgment failed, or their physiology betrayed them.

The Invisible Threats Around Us

When we drive, we don’t interact with vehicles alone.

We interact with human beings whose internal states we can’t see.

The driver ahead may be sleep-deprived. Sleep deprivation after 18 hours of being awake produces reaction times equivalent to a blood alcohol level of 0.05%.2 The person beside us may be under acute stress, experiencing the hormonal variations that can narrow their visual fields and reduces situation awareness. Someone else may be distracted by work, family conflict, financial worry, or physical discomfort.

None of this is visible from the outside. Yet all of it shapes behaviour.

Many have told me that they drove to the appointment in spite of feeling dizzy from new blood pressure medication. Others have driven with severe lower back pain that prevented them from checking blind spots properly. Still others describe driving while emotionally disturbed after receiving bad news… their minds distracted and not on the road.

Human performance fluctuates with fatigue, emotion, attention, health, and situation. Every vehicle around us contains a mind operating under conditions we can’t assess.

Ancient Indian philosophy calls this anitya – impermanence. Nothing is fixed, everything changes moment-to-moment. The driver who was alert five minutes ago may now be drowsy. The road that was good yesterday may have a pothole today. Certainty is an illusion.

And the uncertainty extends beyond people.

On our roads, animals move unpredictably, especially where urban and rural environments overlap. I’ve had to brake suddenly for dogs and cattle on the highway on multiple occasions. Road surfaces change. What’s good in December becomes dangeroud during monsoon. Craters appears without warning. Weather alters roadgrip and visibility.

Driving isn’t merely moving through traffic. It’s managing uncertainty – biological, environmental, mechanical, and psychological – all at once.

Why Your Caution Alone Isn’t Enough

Most responsible drivers do what they should. Speed limits. Seat belts. Helmets. Vehicle maintenance. No distractions. Defensive driving.

These precautions reduce risk significantly. They save lives.

But they don’t eliminate uncertainty and vulnerability.

You can manage your behaviour. You can’t manage everyone else’s behaviour. You can’t control the environment in which you drive. Outcomes depend on the interaction of many factors, not just your own decisions.

Think about it this way: if you exercise regularly, your health improves because of your own actions. If you secure your home, your safety increases because of your precautions.

On the road? Safety is interdependent.

Your well-being depends not only on what you do, but on what everyone around you does… correctly, incorrectly, or unpredictably.

I’ve seen this happen differently in different countries. In countries with low traffic death rates, places like Netherlands and Japan, drivers aren’t born careful. What is different is the system of driving: road design that reduces error, enforcement of rules that’s consistent and not arbitrary, vehicle standards that protect occupants, and a culture that treats road safety as a collective responsibility rather than an individual virtue.

Here in India, we ask individuals to compensate for problems in the system through constant vigilance. It works sometimes. But it’s exhausting. And it fails so frequently that our accident rates are among the highest in the world.

Every day, we see people driving on the wrong side, complaining that roads with dividers are ‘unscientific’ simply because they have to drive a bit longer to take a U-turn. But the fundamental priority of road engineering is the safety of human life, not just our convenience or saving time. The minute or two saved this way could prove deadly to someone coming from the opposite direction.

The Asymmetry We Ignore

This interdependence doesn’t affect everyone equally.

A pedestrian suffers far more consequence from a car driver’s error than the driver does. A cyclist or motorcyclist remains physically exposed even when they are behaving responsibly. Larger vehicles cause graver injury to those in smaller vehicles.

I’ve seen this disparity in the emergency department. When a two-wheeler collides with an SUV, the results are brutal. The motorcyclist develops multiple fractures, internal bleeding, head trauma. The SUV driver walks away with minor bruises or none at all.

Same accident. Very different outcomes.

The road isn’t just shared. It’s asymmetrical.

Those with less physical protection depend even more heavily on the caution and restraint of others. Road safety, therefore, isn’t merely a matter of personal responsibility. It’s also a matter of ethics – recognizing how one person’s risk-taking becomes another person’s injury or even death.

This is karma in its most literal sense. Action and consequence. Not cosmic justice, but physics and physiology. When you drive distracted or dangerously, you don’t just cause risk to yourself. You create consequences that others will bear. Some with injuries on their body, and some with their lives.

We Reached Udupi Safely

After 60 kilometers of vigilance, adaptation, and occasional anxiety, we reached Udupi safely.

My daughter parked, exhaled deeply. “That was harder than I expected.”

I asked what she meant.

“It’s not the driving itself,” she said. “It’s managing everyone else. Trying to predict what they’ll do. Staying alert for things I can’t control.”

Exactly.

She’d discovered what every experienced driver knows but rarely mentions. Safety on the road isn’t something you achieve through skill alone. It’s something you negotiate, moment by moment, through a weak coordination with strangers who have no connection to you and who you’ll never see again.

We were safe because she drove carefully. But also because dozens of other drivers, truck drivers, motorcyclists, auto-rickshaw drivers, car owners, made some good decisions, at the right the time, to let us move without being harmed.

Some of them were probably tired. Some probably distracted. Some certainly in a hurry. But none of them made a dangerous error in the precise moment and location where our paths crossed.

That’s not just good driving.

It’s good fortune. Thousands of micro-level incidents that we never even come to know.

The question my daughter asked at the start, “How much of my safety depends on me, and how much on everyone else?” – has an uncomfortable answer: probably 50-50, maybe even less in your favour.

You can be perfectly careful and still be unsafe.

But the alternative isn’t fear. It’s recognizing that road safety is a collective project that requires both personal responsibility and support by everyone else and the traffic system. That recognition changes how we think about driving, how we behave on the road, and what we expect from the traffic systems that are meant to protect us on our roads.

In the next part of this series, I’ll talk about what individual responsibility actually means when outcomes are shared—and why it’s non-negotiable despite the uncertainty.

About This Series:

This is Part 1 of Sadgati: Safe Passage on Shared Roads, a three-part reflection on road safety.

The goal isn’t to lecture, but to encourage thinking about road safety as both a personal and a collective responsibility.

Dr. Shashikiran Umakanth (MBBS, MD, FRCP Edin.) is the Professor & Head of Internal Medicine at Dr. TMA Pai Hospital, Udupi, under the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE). While he has contributed to nearly 100 scientific publications in the academic world, he writes on MEDiscuss out of a passion to simplify complex medical science for public awareness.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023. Geneva: WHO; 2023. Available at: Link. Accessed: February 15, 2026.

- Dawson D, Reid K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature. 1997;388(6639):235. DOI: 10.1038/40775. Accessed: February 15, 2026.