Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Mechanisms, Interpretation, and Clinical Utility

1. Introduction

The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is one of oldest laboratory tests in the field of medicine. Though it lacks specificity, its low cost and simplicity make it a valuable screening tool. It measures the distance (in millimeters) that red blood cells (RBCs) fall in a vertical tube of anticoagulated blood over one hour.

2. The Mechanism: Zeta Potential vs. Rouleaux

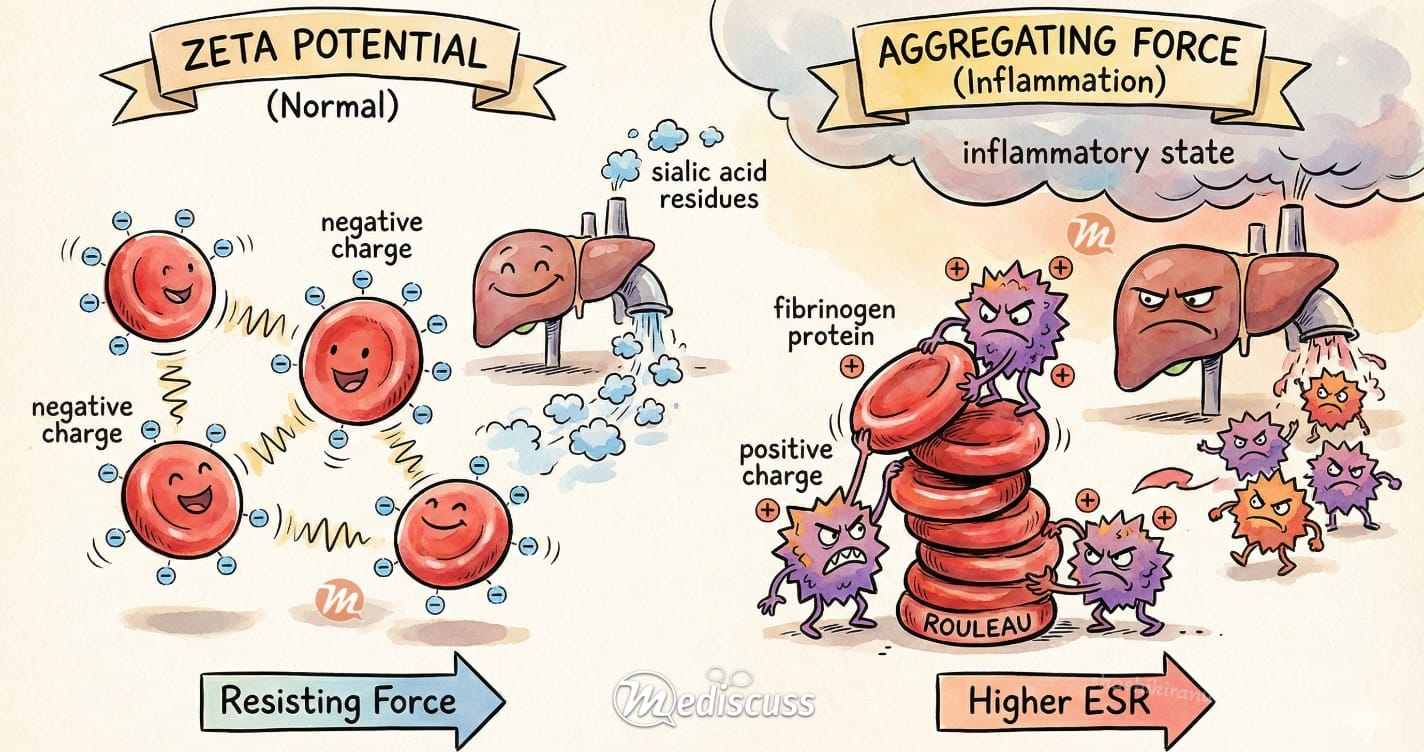

To interpret ESR correctly, we must understand the microscopic forces at play:

- The Resisting Force (Zeta Potential): Normal RBCs have a negatively charged surface (sialic acid residues). This negative charge causes them to repel each other, preventing clumping. This force is called Zeta Potential.

- The Aggregating Force (Plasma Proteins): In inflammatory states, the liver produces acute-phase reactants, primarily Fibrinogen. Fibrinogen is positively charged and neutralizes the negative Zeta potential.

The Result: When the negative charge is neutralized, RBCs stack together like coins. This stack is called a Rouleau. A Rouleau is heavier than individual cells and falls faster due to gravity, resulting in a higher ESR.

3. Reference Ranges & The Age Factor

ESR naturally increases with age and is generally higher in biological females. A universal “normal” does not exist, but the Westergren Formula provides a clinically useful upper limit:

Example: A 60-year-old woman has a normal limit of (60 + 10) / 2 = 35 mm/hr.

4. Interpreting the Results

| Result & Severity |

Clinical Context & Differential Diagnosis

|

|---|---|

|

Mild Elevation

(Slightly above age-limit) |

Often Non-Specific. Common physiological states or mild conditions:

|

|

Moderate Elevation

(~30 – 100 mm/hr) |

Significant Inflammation. Requires investigation for systemic causes:

|

|

Extreme Elevation

(> 100 mm/hr) |

🚨 RED FLAG: Serious Pathology High-Yield diagnoses to rule out immediately:

|

5. ESR vs. CRP: Which one to order?

A common clinical dilemma is choosing between ESR and C-Reactive Protein (CRP).

- CRP: Rises rapidly (within 6-8 hours) and normalizes quickly once the insult resolves. It is more sensitive to acute changes.

- ESR: Rises slowly (24-48 hours) and remains elevated for weeks even after the patient improves (due to the long half-life of fibrinogen).

6. Factors Affecting ESR (False Positives/Negatives)

Since ESR depends on RBC physics, non-inflammatory factors can skew the result:

- Falsely HIGH ESR:

- Anemia: Fewer RBCs mean less repulsion, allowing them to settle faster.

- Kidney Failure: Decreased albumin affects plasma viscosity.

- Falsely LOW ESR:

- Polycythemia: Too many RBCs “overcrowd” the tube and cannot settle.

- Sickle Cell Disease / Spherocytosis: Abnormal shapes prevent smooth stacking (Rouleaux formation).

- Heart Failure: Low plasma fibrinogen levels.

- The Mechanism: ESR is a measure of Rouleaux formation. Inflammatory proteins (like Fibrinogen) overcome the negative charge (Zeta potential) that usually keeps RBCs apart.

- Age Matters: There is no single “normal” value. Always use the age-adjusted formula (Westergren) to avoid investigating healthy elderly patients for false positives.

- ESR vs. CRP: CRP is faster to rise and fall (acute changes). ESR is slower and stays elevated longer (chronic monitoring).

- ESR lag: When treating osteomyelitis or endocarditis, a persistently high ESR despite clinical improvement is common (the “ESR lag”) and does not necessarily mean treatment failure.

- The “Red Flag”: An ESR >100 mm/hr is never normal. It demands an immediate workup for malignancy (especially Multiple Myeloma), tuberculosis, temporal arteritis, metastatic malignancies or deep-seated infection.

- Treat the Patient: ESR is a non-specific screening tool. It should never override clinical judgment or physical examination findings.

7. Conclusion: The Art of Interpreting ESR

Despite the advent of faster markers like CRP, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate remains a valuable tool for the clinician. However, its greatest strength (high sensitivity) is also its main limitation. An elevated ESR tells us that inflammation may be present, but it rarely tells us where or why.

Therefore, the golden rule of ESR interpretation is context. A high value should never be interpreted in isolation or trigger a “wild goose chase” for occult disease in an otherwise healthy person. Instead, it serves as a prompt to review the patient’s history and perform a thorough physical examination. As with all investigations in medicine, the ESR is a support for clinical judgment, not a substitute for it. If you encounter an isolated, unexplained elevation, the wisest clinical decision is often to reassure the patient and repeat the test in 4–8 weeks rather than initiating an expensive and anxious workup immediately.

Dr. Shashikiran Umakanth (MBBS, MD, FRCP Edin.) is the Professor & Head of Internal Medicine at Dr. TMA Pai Hospital, Udupi, under the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE). While he has contributed to nearly 100 scientific publications in the academic world, he writes on MEDiscuss out of a passion to simplify complex medical science for public awareness.